The first three visual essays that I watched were from Helen Evans, Theresa King-Dickinson, and Peggy Hebard.

Written by Lisset Rojo Ramirez

Helen Evans’ Borders was the most interesting to me. Like Helen Evans, I also grew up around the concept of borders. Borders, in the United States, usher much debate that is usually associated with immigration control and restriction. When viewing the birdlike flight sculptures that Evans described, I was reminded of Ai Weiwei’s bird cages. Ai Weiwei expressed the feeling of being restricted by borders through his artwork. Borders essentially create authority, friction, and excitement but depending on the point of view of the opposing countries. Evans views borders as the doorways to freedom. The running through or breakage of such barriers is beautiful, but the question at hand is, what can we do once the barriers are broken? Peggy Hebard discusses the aftermath of breaking her own barriers. Coming from an immigrant family, she was physically and culturally different than her classmates in school. Although she wanted to stay hidden within the shadows of her colorless clothes, she became to also accept the beauty that “abnormality” brought. She saw the value of having a world that a limited amount of people could truly understand. Similarly, art creates worlds that certain types of people can truly sense. Like Theresa King-Dickinson stated, knowing and understanding the background of situations and, more specifically, artwork, can lead to greater discovery and intimacy with people, or the artist. In other words, art is as binding as culture or language, because in itself lies a certain culture spoken through a unique language. As such, much more can be appreciated if there is a more complex connection in the presence of art. I also wish to be able to create this type of connection with the artist and the subjects of the art when visiting the museums and streets of New York City.

The second three visual essays that I watched were from Enrique Chagoya, Nicola Lopez, and Alejandro Cesarco.

There are different ways in which to communicate with artists. Nicola Lopez has, I believe, an interesting way of communication that I would have never thought existed. She explains how art medium is also an intimate view into the process, thinking, and studio of the artist. In noticing the subtle messages left unknowingly behind, one is able to experience the humanity of the artists. The “mistakes” in a way become essential to the piece. Likewise, our own faults and transgressions make up the human experience and identity that we have. Without them, we would be meaningless without uniqueness and character. Even so, Enrique Chagoya points out that “the human experience transcends through history” which is yet another reason that we, as spectators, are able to have that intimacy with the artist. I also believe that we all share common situations that reflect upon our humanity. For instance, artwork often times hits our nerves and makes us uncomfortable making us think of situations without necessarily solving them. Nevertheless, power ensues from the imagery that we see probably because we share experiences no matter our skin color, language, or religion. This is what makes art so powerful. Alejandro Cesarco also speaks of power but in the location of the artwork itself. He question whether these feelings that rise from art are due to the projection of the artist or a projection of ourselves onto the work. In other words, is the art ever fully articulated or do we just make things up? Even though we could all have the same human experience, there are other more individual experiences that open up new doorways for us to enter. In going further into details, we achieve more complex definitions or interpretations of the work. But who can ever say that there is a single right answer and if it was manipulated due to setting? Asking these types of questions are very important in looking at art. These are the types of questions that I hope to keep asking as I am presented with artwork in a variety of different ways with different emphasis.

At the MET I would like to see the Golden Kingdoms Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas exhibit. In the exhibit, I would like to see and engage the piece called the Octopus Frontlet. It is a Frontlet from Peru made out of gold, chrysocolla, and shells. It is a really interesting and grand piece that seems powerful yet frightened. The exhibit itself is full of treasures from ancient Americas that are unique to a different culture. I would like to engage with it and explore the things in it that were made in another time yet maintain to be ageless. The exhibit is located in Gallery 119.

As I was making my way through the first floor of the Metropolitan Museum, I was surprised to find numerous artifacts of varying magnitudes. The Egyptian hall in itself blew my mind. The amount of space given to such ancient civilization was astounding. It was no surprise that I spent most of my time there- specifically in Hatshepsut’s gallery of sculptures. Thus, I decided to engage with her statues and unearth her true story.

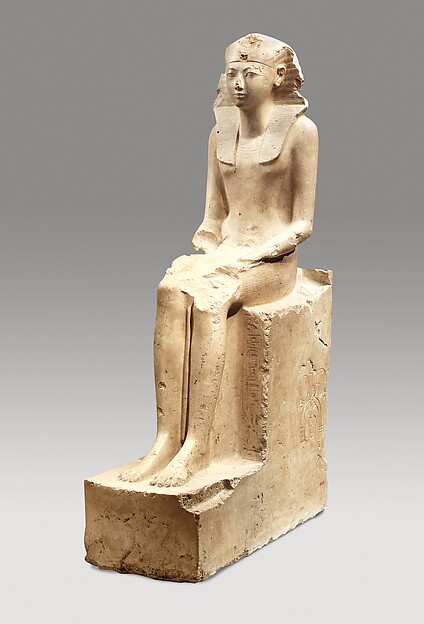

Coming from the great Temple of Dendur exhibit, one expects the great pharaohs of the time to uphold a dominant stature — fierce and powerful, a reflection of their grand tombs, temples, and structures. Such is the reason when upon entering the gallery, I focused entirely on the large busts and head of a seemingly important historical pharaoh- muscular arms and legs kneeling with offering to the gods, a bearded prince bejeweled from head to toe, an honorable man in a position of power. No one would have suspected that such pharaoh was indeed a woman. Her least masculine statue centered the entire room.

Hatshepsut sits 76 inches tall with a width of 49 inches. This was the most life-like and feminine figure in the entire gallery, I wondered whether this limestone carving portrayed her true face, her true figure, her true identity within the compounds of her palace. She sits upon a pedestal-like throne with her hands in her lap and her feet planted firmly on the ground. She wears no shoes but only a shendyt-kilt. Her upper body is exposed blending into a lean masculine figure before reaching her face. Her nemes-headcloth, worn typically by male Egyptian kings, rests on her shoulders and chest. Without the long gone paint, her yellow complexion is young, feminine, and bare faced. She looks like a young teenage prince, yet to grow into the role of an Egyptian King. The figure does not look entirely right but also not entirely wrong. The poised sitting with legs together and hands in lap take me off guard, it is a posture I have been accustomed to. She remains motionless as the years have chipped off the smoothness of her legs and the weather cracked the foundation of her throne.

Hatshepsut was very successful as a female monarch. She was not originally in line for the throne and would have never gotten the chance to become king if her husband (and half-brother), Thutmose II, did not die at a young age and left a small son (of his second wife) behind. Hatshepsut took over for her nephew and continued to rule even after he became of age. She officially adopted the the title of pharaoh claiming her lineage as daughter of Thutmose I, however, many of her monuments feature her presence in a male form.

Most often than not, her monuments were defeminized both in writing and in physique. This may be because of the stigma associated with women rulers in a traditionally male-dominated world. Even though she accomplished much more than her late husband, many were angered at the thought of having her as pharaoh. Consequently, many of her statues were destroyed and thrown away. This unusual monarchy may be the reason why many of Hatshepsut’s figures represent a male king instead of female. She was trying to lessen the argument and fit into the traditional standards of the pharaoh. She would often use her name in a masculine form and dress like a male king. The structure of the Seated Statue of Hatshepsut depicts her internal struggle to maintain an image yet be as she is.

When I saw this work, I was mesmerized. It was someone trying to fit into something society had constructed and no matter how much hard work or dedication went into their work, they were still not entirely accepted. As a woman at a woman’s college, I feel strongly for the under-representation of race and gender whether that be in the professional environment, in the media, or simply in the world. This feeling of “things aren’t right in the world” or inequality has been developing much over my time here at Agnes and has made me truly think in a more global perspective. Throughout the Met Museum, I saw more than just people in paintings but also people with lives, people with stories to tell. I believe art is a form of communication that few can truly understand but powerful because words are often not needed. When I saw Hatshepsut, I wanted to tell her story because her story is much like mine, much live ours- living in a male-dominated life intertwined with ancient traditions that seem to hold us back, to keep us in a box, to prevent, like Beyonce put it, for girls to “rule the world.”

Sources:

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544450?pos=2&ft=Hatshepsut&offset=0&rpp=20&pg=1